Tam, K C H (2012). ‘Developing a new curriculum in communication design: challenges and opportunities’ (in Chinese) in the proceedings of Crossover/Comprehensive symposium, Hangzhou, China, 181–189. (This article was published in Chinese. This is the original manuscript written in English.)

Download full text in PDF format

Abstract

The graphic design discipline has witnessed rapid technological developments and evolving contexts in the past two decades. In order to address the challenges presented by an increasingly knowledge-based society, the School of Design at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University has developed a new four-year BA (Hons) in Communication Design degree programme. This new curriculum situates what is traditionally known as graphic design – a largely medium-specific and artefact-driven discipline – under a purposeful, user-centred framework, putting communication squarely at the centre of the discipline. A conscious move away from the realm of visual arts, this new curriculum has given the discipline a renewed sense of identity and has reconsidered the role of a communication designer not only as a form-giver, but also a strategist, planner as well as system creator for tackling complex communication problems

Introduction

Background

In the last few years, the School of Design at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) has been developing a new four-year undergraduate degree curriculum in communication design. Due to launch in September 2012, this new curriculum aims to address the new challenges and opportunities presented by a society that is becoming increasingly knowledge-based. This new curriculum situates what is traditionally known as ‘graphic design’ – a largely medium-specific and artefact-driven discipline – under a purposeful, user-centred framework, putting communication squarely at the centre of the discipline. It is a conscious move away from the realm of visual arts, which often emphasises on individual approaches and personal intuition. This paper is intended to discuss the philosophy, design rationale and curriculum structure behind the new BA (Hons) in Communication Design degree programme, and to provide discussion points for future development of the communication design profession.

From three years to four years

The PolyU School of Design currently offers a three-year BA (Hons) in Design degree in four disciplines: Advertising Design, Environment & Interior Design, Industrial & Product Design and Visual Communication Design. Common subjects are shared between the four disciplines, as are programme administration and assessment schemes. The current programme structure was implemented in 2005 and has now been running for seven years. In accordance with the Hong Kong SAR government’s region-wide education reform, all university undergraduate degree programmes will shift from the current three-year model to a four-year one in the 2012–13 academic year. Work began in 2008 to redevelop these disciplines into new four-year degree programmes. Spearheaded by the leaders of the four disciplines, the curriculum reform was a long process of planning, review, negotiation and validation. At the time of writing, this process is nearing completion and the programmes are ready to launch in September 2012. The previous Visual Communication Design discipline has been restructured and renamed as a BA (Hons) in Communication Design degree. The new curriculum will be implemented in phases during a three-year transition period, with an additional cohort of 24 students admitted to year one. The first cohort to complete the full four-year curriculum will graduate in 2016.

Practical constraints

Credit distribution

Under the new four-year structure, the number of credits will increase from 96 to 126, of which 29% (36 credits) will be general university requirements intended to broaden student’s scope of knowledge in non-design areas. 59% (75 credits) will be dedicated to subjects specific to the Communication Design discipline. This credit distribution is imposed by the University and had to be taken into consideration when developing the new curricula.

Background of prospective students

70% of the students currently admitted to year one have already had one to two years of sub-degree education in design, via the large numbers of public and privately-funded higher diploma and associate degree programmes. 30% are admitted into the programme with little to no prior training in design, directly after their seventh year of secondary education through the A-level public examination system.

With the future four-year programme structure, all of the students admitted to year one will be from the new Diploma of Secondary School public examination system, having completed six years of secondary education. This means that students will be one year younger than previous applicants, all with little to no experience in design. More places will be offered for direct admission to year three, which are mainly taken up by graduates of sub-degree programmes.

Being a programme funded by the University Grants Council of the Hong Kong SAR government, the intake quotas are somewhat limited and are allocated judiciously on an annual basis by the Council.

Medium of instruction

As mandated by the University, all undergraduate programmes at the PolyU School of Design are taught in English, with the exception of Chinese language subjects. While local students begin to learn English at a young age, English is not their native language. Students’ English language abilities are quite varied and individual tutorials are sometimes supplemented by Cantonese if the tutor is able to speak it. While using English as the medium of instruction is an advantage for developing an international outlook, it could also mean that students receive somewhat less exposure to Chinese culture.

Curriculum philosophy: defining an evolving discipline

The term ‘graphic design’ and its many permutations

The term ‘graphic design’ was coined in 1922 by American artist–designer William Addison Dwiggins to replace the term ‘commercial art’, which has its roots in decorative and applied arts. While graphic design has since been a common identifier for the discipline, a plethora of alternative terms began to appear in the past two decades. ‘Visual communication’, ‘graphic communication’ and ‘communication design’ are some examples. These alternative terms reflect attempts to address the changing contexts of the practices of graphic design, or may show a desire to elevate the status of graphic design beyond mere styling. In the industry however, the term ‘graphic design’ is still the most widely used.

‘Graphic design’, ‘visual communication’ as well as ‘graphic communication’ are terms that emphasise the means of communication. While ‘visual’ and ‘graphic’ may seem similar, they are distinct from each other. ‘Graphic’ implies a combination of the visual as well as the verbal, forming a symbolisation system, while ‘visual’ is more general and refers to anything that can be taken in by sight. In Chinese, graphic design translates as ping mian she ji (平面設計), literally ‘flat surface design’, which refers to the two-dimensional nature of the discipline. All of these terms are constrained by the medium or means of communication and focus on the artefacts produced rather than the process of communication itself.

Technological influence: printing

Printing technology has been inextricably linked to the practices of communication design: from woodblock printing to letterpress to lithography and digital printing. Paper, as a cheap and portable medium, has been fuelling the advances of the printing industry, and has been the single most important medium for communication designers to work with for centuries. Mass production of information has always been at the heart of the discipline. To this end, text (as opposed to images) plays an extremely important role. The invention of moveable type printing was a defining moment in the history of human communication, which enabled the industrialisation of the dissemination and preservation of knowledge with highly improved efficiency and enormous scale. With the wide adoption of desktop publishing since the 1980s, the traditional roles of the printer and the graphic designer are being redefined as the communication designer is now able to handle typesetting, image processing and the generation of press-ready artwork without leaving one’s desk.

Technological influence: digital technology

The proliferation of the internet since the early 1990s and the rapid growth of mobile devices and related technologies in recent years are transforming the way we navigate and interact with information, knowledge, environments and above all, people. Digital technology has gone far beyond being a mere tool for visualisation and production; it is the very means through which people communicate and has become a way of life. With Web 2.0, the semantic web, mobile networked devices, location-based services and beyond, users are also generating vast amounts of information and knowledge. The flow of information is no longer top-down but in a networked manner that is shared by everyone.

These digital technologies gave rise to new disciplines such as multimedia design, web design and human–computer interaction design, which focus exclusively on these digital media. A communication designer may also play an active role in strategising, structuring and visualising information for these media. Communication in this context is no longer the simple case of a message delivered to a passive audience, or porting content from one medium to another. The processes becomes much more complex, requiring an acute awareness of user behaviours and systems thinking. Instead of producing simple visual representations of ideas and standalone artefacts, designers are now likely to be called on to create tools, systems, services as well as experiences. This technological shift presents communication designers with unprecedented challenges and opportunities. John Heskett (2011) writes:

‘The result [of the shift from mass to flexible technology] is that designers are no longer simply the manipulators of visual form (although many will continue to perform this role). In addition, however, many other designers are becoming responsible for creating and implementing systems that enable users to determine for themselves how they will be used and implemented in their lives and work. In addition, new functions for design at the level of planning and strategic management are opening up. This provision of flexible resources on a massive and complex scale opens up new and powerful possibilities in technology, production and economy, and for new approaches to design, the potential for which has barely begun to be tapped.’

Designing in a knowledge-based society

As our society and economy become increasingly knowledge-based, communication comes to the fore as an essential activity in every facet of our lives. Much of this communication is manifested through visual and verbal means, but may also involve other human senses, delivered via a variety of media to form complex communication experiences. These experiences enable users to sieve through, learn and share information, make appropriate choices, accomplish tasks and, at a deeper level, reflect on who we are as members of our cultures and communities. In this context, communication designers not only have to possess aesthetic sensitivity and an intuitive ability to think creatively, but managerial, planning and analytical skills for tackling complex communication problems have also become essential.

The production of tangible artefacts is at the centre of most design practices. Designers are usually concerned about the material quality and aesthetics of the artefacts that they produce. There is nothing inherently wrong with this, and much communication is still accomplished via the production of tangible artefacts. But it is important to take a step back and consider the processes that influence understanding and how they engender desired actions on the user’s part through the use of artefacts. Artefacts, therefore, play an intermediary role in such cognitive processes and resulting actions.

Despite frequent declarations announcing the demise of print, much communication is still published in the printed format, and communication designers continue to engage in designing for print. However, it is vital that communication designers assess which medium or channel of communication is the most appropriate and effective for a given purpose and audience, rather than defaulting to print media.

As communication technology continues to advance and our world becomes ever more connected, graphic design education and practices need to evolve in order to meet the new challenges and opportunities that arise in these new circumstances. The term ‘communication design’ accurately captures the essence of the discipline and calls for a renewed set of skills and knowledge that enables designers to think in strategic, systemic and innovative ways.

Theoretical models

One of the major threats to communication design lies in the difficulty of measuring the success of a piece of work. Is it based on visual impact? Craftsmanship? The originality in its visual style (something that the world has not seen before)? Or should it be based on improved business returns? There does not seem to be an agreed set of criteria for evaluating the success of a piece of communication design. From a survey of 1,500 US graphic designers conducted by Paul Nini (Nini 1997), it was found that large percentages of respondents do not seek user input during the concept development stage, nor solicit user evaluation of communication prototypes and final design communications. Nini writes:

‘My experience in, and observation of, the field [of graphic design] seems to suggest that graphic designers are quite adept at designing, producing and introducing solutions (as designed messages), but that these are based on little if any information gathering and analysis. Likewise, it is rare to find graphic designers who solicit end-user evaluation of their efforts, whether in prototypical or final form.’

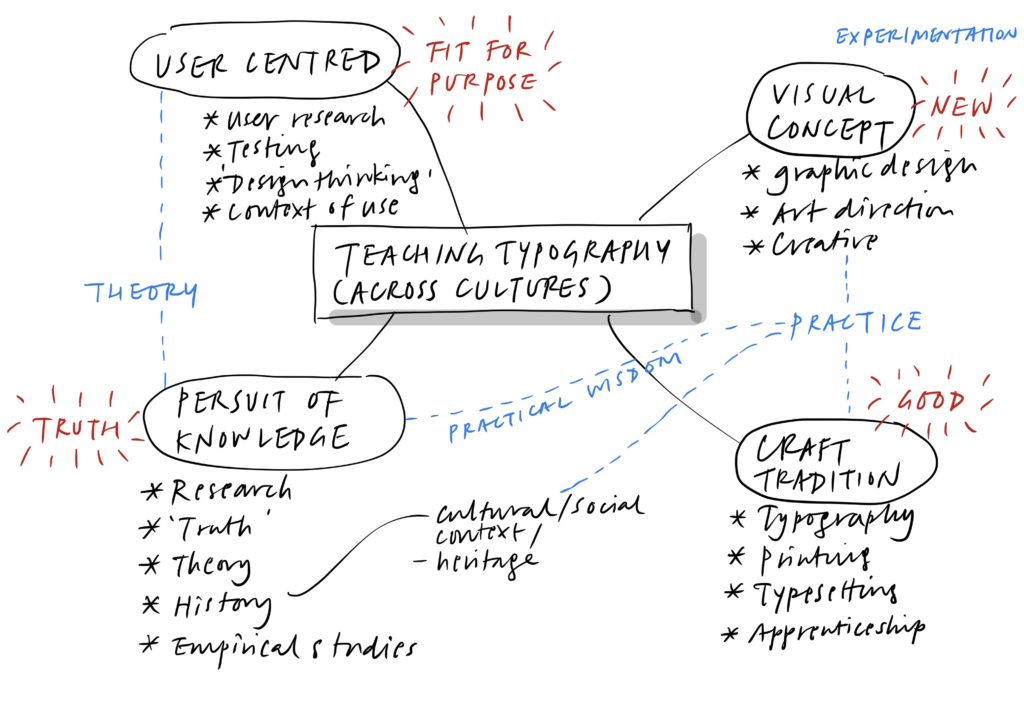

Communication design, like other forms of fine and applied arts, is often dismissed as self-expressive. It is important that more objective frameworks are established to gauge the effectiveness of communication design, so that professionalism is assured rather than relying on a designer’s reputation and fame. Shifting communication design from a designer-oriented activity to a user-centred one is therefore essential. The following three models have been useful for communication design students at the PolyU School of Design. Although the concepts behind these models sometimes overlap, they provide ways to situate the practices of communication in wider contexts and offer a holistic and all-encompassing perspective on what communication designers do.

Syntactic, semantic, pragmatic

The model for semiotic analysis devised by Charles Morris in 1972 provides a good framework for evaluating any communication design products. Students are encouraged to evaluate their peer’s work not only based on their subjective feelings or artistic preferences but in a more holistic, objective manner.

The syntactic level deals with form – the use of visual elements and principles in creating a graphically coherent design piece. Of the three levels, this one is the most familiar to students as well as most practicing communication designers, as it is primarily concerned with how a design piece looks. ‘Process schools’ that are based on the Swiss model of graphic design teaching work mainly on the syntactic level and encourage students to experiment with form, combining imagery and text in inventive ways to create engaging graphics. This method alone is wholly inadequate in assessing a communication design piece, as its main focus is on aesthetic concerns.

The semantic level is about content – the meanings conveyed to the audience in terms of visual as well as verbal language. Through the symbolisation methods used and the structure and organisation of words, images and graphical forms, meaning is derived by the audience. The audience’s ability to decode linguistic and cultural codes highly depends on how much of these are shared between the originator of the message and the audience or user. Ambiguity should be kept to a minimum and clarity in communication on a semantic level should be sought.

The pragmatic level pertains to context – the purpose of the communication, who it is designed for and how effectively it performs in serving its purpose. The pragmatic level is primarily about performance and suitability for purpose; whether the audience or user is able to perform the desired tasks accordingly after viewing and/or using a communication design piece. Pragmatic concerns are implicit in disciplines such as industrial and environment design but are often overlooked by communication designers. Usability studies, psychology of learning, user-centred research, legibility studies, etc. contribute to pragmatic considerations, helping communication designers in making informed design decisions, lending credibility and value to the work t

Physical, cognitive, affective

Another model, a three-part framework for information design (Carliner 2000) is also very useful for communication designers. Carliner suggests that there are three technical levels that should be considered, namely, the physical, cognitive and affective. Carliner writes:

‘[ . . . ] design is a problem-solving discipline. It considers more than the appearance of the designed product, but also the underlying structure of the solution and its anticipated reception by users. Because design is focused on solving problems, a design theory must provide more than a series of guidelines about discrete characteristics of the solution; it must focus designers on identifying and considering the interrelated issues that must be addressed in a solution.’ (Carliner 2000)

The physical level helps users to find and locate information that is of interest or relevance to them. This level considers issues related to the physical properties as well as the organisation within a design artefact.

The cognitive level considers whether users are able to understand and make use of the information once they find it. This level is concerned with the processes of visual perception and cognition, and how ‘performance goals’ are achieved.

The affective level is concerned with motivating users to perform their intended tasks after finding and understanding the information. This has to do with the emotional response that a communication product is able to elicit from its users, so that their attention is captured and they are motivated to act accordingly.

Visceral, behavioural, reflective

In the book Emotional design, Don Norman (1999) suggests a three-level model for processing and design: visceral, behavioural and reflective. All three levels work together to form a user experience that is significant and meaningful. The visceral level relates to the immediate sensorial response when a users first interact with a designed product. It is concerned with the aesthetic appearance of a product and the ability to generate an emotional response towards the product. The behavioural level is about the function and usability of the product, how easy is it to understand and interact with it in order to achieve the tasks intended. The reflective level focuses on the connotative or associative meanings of a designed product and involves deeper meanings such as status, prestige, beliefs etc.

These three models, form a robust theoretical basis for formulating a clear philosophy that underpins the new curriculum. Ideas in these models underpin the programme learning outcomes as well as the curriculum structure.

Programme learning outcomes

As stipulated by the university, we adopt an ‘outcome-based’ approach to teaching and learning at the PolyU School of Design. Also known as ‘constructive alignment’ (Biggs and Tang 2007), this approach is student-oriented rather than teacher-centred. Instead of viewing the curriculum simply as content areas that need to be covered by the teacher, the outcome-based approach begins with planning sets of competencies (learning outcomes) that students are expected to achieve, and then deciding what areas of knowledge are required and what assessment tasks are able to indicate these competencies. Demonstrable outcomes are developed at the programme level with a more general view, and are further broken down into more specific outcomes developed for each subject at each stage of learning.

A set of nine learning outcomes have been developed for the Communication Design programme. These outcomes are intended to be comprehensive, with the aim to graduate not only competent job-ready professionals, but practitioners who are resilient in the face of change, with a vision to advance their careers and themselves become agents of change. The outcomes listed below encompasses traditional as well as contemporary values in a knowledge-based society. Subjects in the curriculum are organised in such a way that systematically address these outcomes at various stages in a student’s learning. On completion of the programme, it is hoped that students will possess the following competencies:

Professional competencies

- Situate the practices of communication design within social, cultural, sustainable, technological, business and professional contexts

- Adopt a user-centred approach to communication design through the application of appropriate research methods to the understanding of contexts and users in order to make informed design decisions

- Adopt an iterative design process that involves divergent and convergent modes of thinking; to think creatively, strategically as well as systemically in solving communication problems

- Shape communication experiences for a variety of media through typography, imagery, interactivity and time with sensitivity to aesthetics and craft

- Reflect critically on the practices of communication design and anticipate future developments of the profession in local and global contexts

Generic competencies

- Communicate with clarity and conviction via verbal, written and visual means

- Approach problems critically from multiple perspectives; assess needs, identify opportunities, question the status quo and substantiate arguments

- Work independently and collaboratively, manage projects and deadlines

- Be inquisitive and sustain a passion for lifelong learning

Curriculum design

The new curriculum in communication design is based on the notion that graduates should be equipped with the professional skills necessary to meet current and future needs of the industry in Hong Kong, as well as a critical mind that will enable them to question the social and cultural roles of communication design in local, regional and global contexts.

Teaching and learning modes

The master–apprentice approach

Learning by doing has been the norm in design education where students experiment with visual concepts, manipulate visual forms and come up with creative solutions. An iterative process is encouraged, where students generate numerous concepts before deciding on one, which is then further developed into a final solution. Finding an original concept or visual language is often the main concern, aside from the purpose that the brief is destined to serve. Teachers work with students in a studio environment in a master–apprenticeship mode. Students are often encouraged to develop an individual approach or style. This mode of teaching has its roots in visual art education. While learning by doing is still relevant in today’s practices of communication design, by itself it is insufficient as the complexity of the problems that communication designers encounter continue to increase.

Balancing tacit and coded knowledge

Tacit knowledge is accumulated by continuous practice, and it must be complemented by a structured body of coded knowledge, providing a theoretical basis to what we do as communication designers. This is important for communication designers so that they are able to make educated, informed design decisions and are able to substantiate arguments in front of clients.

It is important to not only put emphasis on the know-how of design, but also the know-whys as well as the know-whats. In other words, we challenge students to consider why a design should exist in the first place, what situation and who they are designing for, what to design, and finally how to go about designing it.

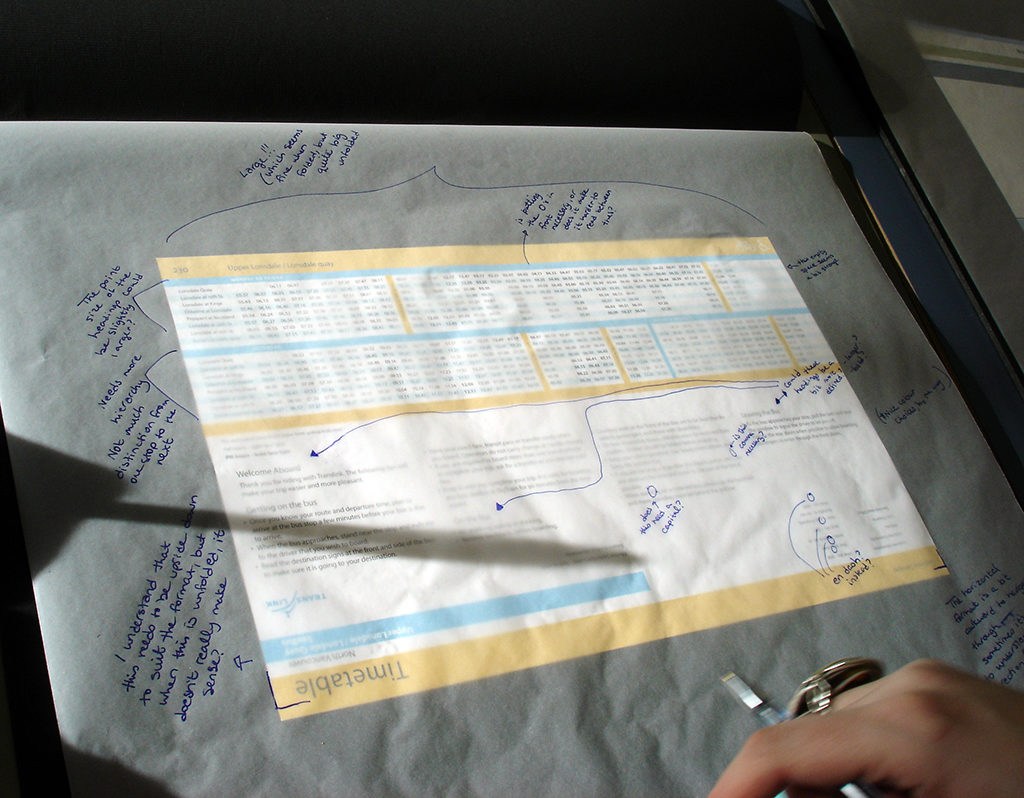

The role of research

Under a user-centred approach to communication design, research becomes a crucial activity for designers to gather knowledge about the users and contexts that they are designing for. Successful designs are not based solely on the designer’s assumptions or hunches. Careful consideration must be made regarding the context of use; the situation or series of activities that people experience when they encounter, interact with and make sense of a communication product. Collection of primary and secondary data as well as the analysis and synthesis of the data gathered generate insights and conclusions which help designers immensely in identifying issues and problems and informing their design decisions. Research at the undergraduate level should focus on this mode of research, which is pragmatic and closely linked to studio practice. In the new Communication Design degree programme, research methods and theoretical knowledge are introduced in a seminar subject that runs parallel with studio subjects.

Studio practice and teaching

Much of the teaching and learning happens inside each year group’s studio space, a designated place that is a vital part of a communication design student’s life. Students work both individually and collaboratively in the studio where they share knowledge and resources, generate concepts, make and test artefacts, engage in discussions and debates as well as charting their processes. These spaces are vibrant and active communities of practice.

Workshops and tutorials

Workshops and tutorials, which are intended for building tacit knowledge and skills, are usually held at these studios. Teachers teach by example through demonstrations and participating in discussions and debates.

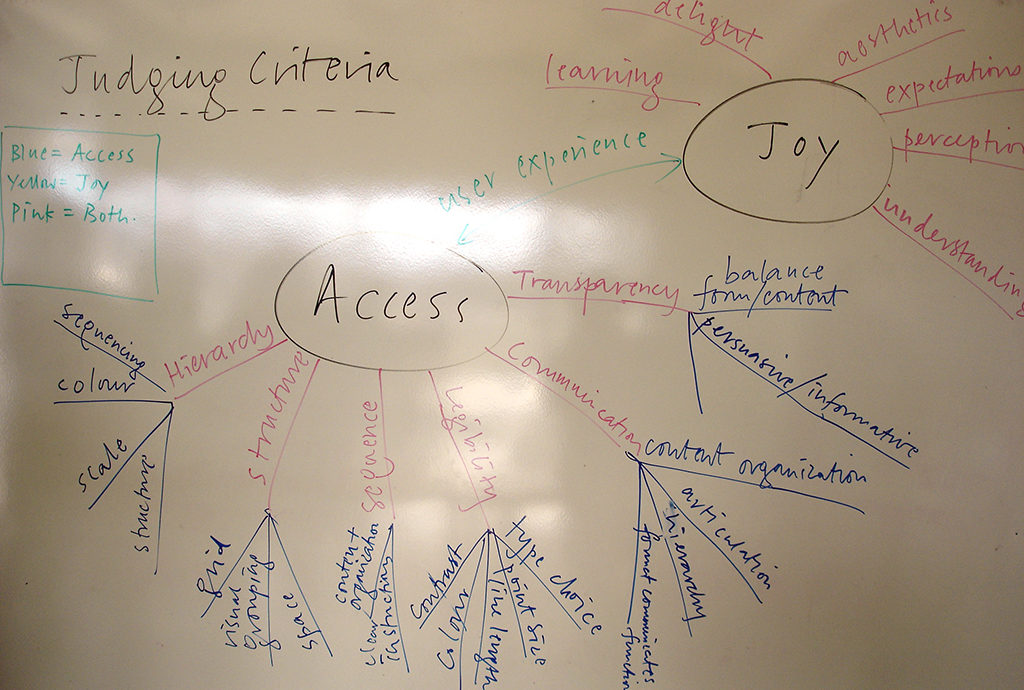

Critiques

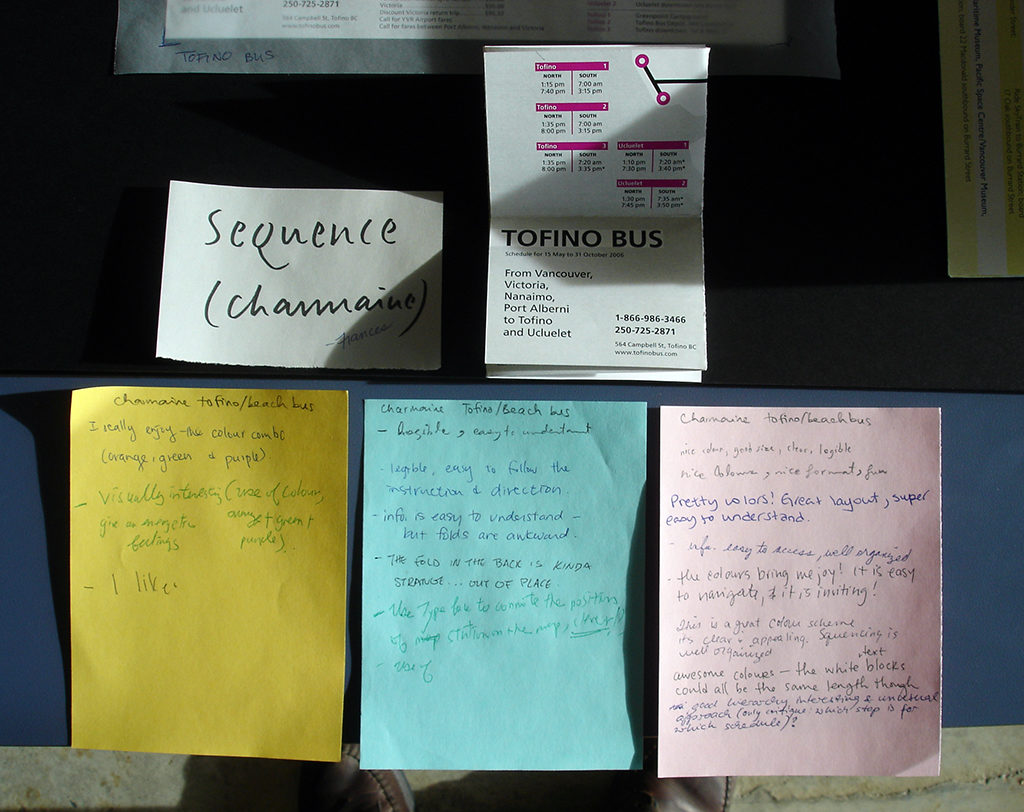

Critiques are an important component of studio learning. Before students present their work, frameworks with criteria are established for objective evaluations of the projects. Students can hence assess the effectiveness of the work from different perspectives and learn from the strengths and weaknesses of their peers.

Seminar- and lecture-based subjects

History, theory, research and other contextual topics are typically taught through lectures and seminars. Lectures may be followed by workshops that reinforce the concepts introduced. Topical readings and case studies are discussed and debated amongst students and tutor.

Three key stages of learning

The four-year curriculum is divided into three key stages of learning. The first stage focusses on making and developing fundamental skills in visual–verbal language, with an overview of the discipline, underpinned by historical and theoretical discussions. The second stage involves studio practice informed by context, where fundamental skills are integrated and applied in lifelike projects, with further studies in history, theory and culture. The third stage emphasises the synthesis of skills, methods and concepts and prepare students for professional practice, working collaboratively as well as independently. The curriculum consists of 38% practice-based subjects, 21% context-based seminar subjects, 12% electives and 29% general studies required by the university.

Stage one: building tacit knowledge

The first stage of the students’ learning is dedicated to developing students’ tacit knowledge. Five key areas are identified as fundamental to the learning of communication design: typography, drawing, images, time and interactivity. Mentions of specific media are deliberately avoided in the subject titles, as they are likely to evolve over time; though students will be developing affinities to a wide variety of different media. Emphasis is placed on the application of these skills in lifelike communication contexts and the interrelations between them.

Typography, drawing and images are traditional skills in graphic design, while time and interactivity are new additions and are mandatory subjects. Time deals with storytelling and sequential narratives, most likely to be applied to motion graphics but also essential in communicating design scenarios. Interactivity deals with interface design, how users interact with and manipulate information for digital devices as well as physical interfaces.

These fundamental subjects are complemented by seminar subjects that lend a theoretical perspective to studio practice, such as media, information and visual literacy, emerging issues of the discipline, the role of research in design as well as visual culture and design history.

After gaining fundamental knowledge and skills in their first year, students then move on to integrating these skills in two specific directions: information design and art direction. These are intermediate level subjects that act as bridges to subsequent contextual studio projects in stage 2 below.

Stage 2: contextual studio projects

There are four themed contextual studio subjects: (1) Text & Image, (2) Information, (3) Identities and (4) Experiences. With the exception of Text & Image, contextual studio subjects are supported by concurrent seminar subjects that introduce research methods and theories related to the studios’ themes, such as user research methods, brand strategy and cultural identity.

The themes of these studios were chosen to address the core issues that the communication design discipline is concerned with. Text and image is concerned with the shaping of simple messages using words and images. Information concentrates on lending clarity and accessibility to complex information. Identities is about strategising and building visual systems that reflect the identities of cultural, social and commercial communities. Experiences deals with the creation of complex communication experiences with many different components such as product–service systems. These studio projects begin with the simple problems gradually build up in complexity.

Students may choose from one of several briefs related to the theme of the studios, led by one faculty member whose role is similar to a team leader or manager. Real-life projects could be brought into these studio subjects, and the intention is to make these studio experiences as close to professional practice as possible.

While designing for persuasion is also a possible theme, it is somewhat deemphasised in the Communication Design programme, as advertising is offered as a separate programme at the PolyU School of Design.

Stage 3: professional practice preparation

The final stage of learning is intended to prepare students to enter the professional workforce upon graduation. Students will have the opportunity to work collaboratively in an interdisciplinary team on a real-life project, and embarking on a substantial self-directed final project after an intensive study of a topic of their choice. It is worth noting that students are encouraged to explore issues that are contextual and of relevance to the needs of the society in their final project investigations. They are encouraged to think beyond a particular medium of expression and steer away from overly personal topics.

Future challenges and conclusion

This paper has outlined the many changes and new challenges that the communication design discipline is currently facing and how the conceptualisation and design of a new curriculum has addressed some of these issues. The successes and failures of this new curriculum design philosophy have yet to be proven when the first batch of students graduate in 2016 and enter the workforce as a new breed of designers. There are many uncertainties that lie ahead both within the Greater China region and around the world as the economy continues to evolve and the definitions of the profession continue to expand.

One of the major challenges for the communication design profession is its fragmented identity. The lack of a unified body of disciplinary knowledge makes it more difficult to draw the boundaries of the profession and to agree on a definitive set of knowledge and skills that communication designers should possess. In turn, people outside of the profession has formed superficial assumptions of what graphic or communication design means. As much as design academics have continued to engage in debates about the core issues of the discipline, the graphic design industry is rather insular and slow to respond to change.

As higher education becomes more expensive and commodified, undergraduate education becomes increasingly career-driven. There is pressure from institutions, potential employers as well as students to be more career-minded. Producing immediately employable designers who possess all of the necessary form-making and technical skills that match the existing rules of the game seems to be the norm. The idea of success under this frame of mind constitute the winning of design awards that mostly reward style over substance and effectiveness, and the relentless pursuit of stardom in the design world. This potentially has a negative effect on the growth of the communication design as a profession in the long term, if our ultimate goal is to improve human conditions through designing communications. The working definition that Jorge Frascara (Frascara 1995) offers for graphic design eloquently stresses this: ‘graphic design is the activity that organises visual communication in society. It is concerned with the efficiency of communication, the technology used for its implementation, and the social impact it effects – in other words, its social responsibility’.

A university-based education in design certainly has the responsibility to go beyond professional know-hows and embark on critical debates of the present as well as future of the discipline. Nurturing visionaries and change agents who are critical in thinking and broad in their scope seems to be far-fetched for the industry, but absolutely necessary if universities are to continue to be cradles of academic discourse and proponents of the advancement of any profession. It is hoped that the curriculum design philosophy presented in this paper would give rise to a renewed identity of the discipline that will transpire further debates and developments in the practices and education of communication design in China and beyond.

Bibliography

Carliner, S. (2000). ‘Physical, cognitive and affective: a three-part framework for information design’ in Technical Communication, fourth quarter 2000, pp. 561–576

Frascara, J. (1995). ‘Graphic design: fine art or social science?’ from Margolin, Victor and Buchanan, Richard (eds.) The idea of design. Cambridge MA: MIT Press

Heskett, J. (2011). Continuity and change, design for Hong Kong: a strategic review of design education and practice. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Nini, P. J. (1996). ‘What graphic designers say they do’ in Information Design Journal, volume 8, number 2, pp. 181–188

Norman, D.A. (2004). Emotional design: why we love (or hate) everyday things. New York: Basic Books